Supporting Children Through Loss

- Katherine Walsh

- Apr 22

- 4 min read

A rollercoaster does not do it justice.

I've even struggled to work this into a cohesive piece as I'm quickly learning that grief is not cohesive, eloquent, or tidy.

But here’s some attempt at fluency (I was a teacher after all!):

What I've learned about children through my shared experience of grief with a 6 and 7 year old:

Some children may be really articulate and happy to talk about everything they're experiencing from bitter sadness to fond memories. [My eldest.]

Some children won't – or at least, not directly. But with those that don't, you need to become a detective! The brain's stress response can make it difficult for children to verbalise complex emotions, even when they're feeling them intensely. [My youngest.]

Behaviour is communication - heard, understood & dealt with a million times in teaching (& the many hours of safeguarding, behaviour, teaching skills training) but when it comes to our own little ones, in stressful times that can be forgotten. My typically well-behaved girls have been downright brutal at bedtimes and with each other lately. Is it grief? Easter holidays? Normal development? Probably all three colliding in a perfect storm.

Tough bedtimes mean something. Being on the receiving end of my daughter demanding another book, shouting at me, incoherently shouting ‘bad words’ at her sister, refusing to go to her bedroom etc. was sending me irate internally, but, it turns out this was because she was having nightmares and was scared to go to bed. I know now that research shows sleep disturbances are common in bereaved children, with their brains processing trauma during vulnerable night hours.

Temporary amendments to bedtime routines: The girls wanted to sleep in my bed, they said they knew I'd say no, so I surprised them & said yes! I had it in mind that I'd do it for a few days, maybe a week. But one night was all it took! 1 night of us all getting into my bed gave them the security they needed to then (voluntarily) just go to their beds the following night happily. The science backs this up – feeling physically safe helps regulate their nervous systems.

Talk talk talk talk. Talking helps. Answering questions honestly helps. Not beating around the bush helps. Not leaving them with any element of confusion helps. Children's imaginations will fill in the gaps with something far worse than reality if we're not transparent.

Use the terms dead, death, died. Not lost, gone away, left us, gone to heaven (unless you are religious I guess). As hard as it feels, they do better from full transparency where there is no residual confusion. Developmental psychologists are clear on this – concrete language prevents the magical thinking that can lead to confusion or self-blame.

In child-friendly ways, talk about what happened - she had a heart attack, fell & hit her head very badly. Make it clear it was extreme so they don't then think (and worry, without you knowing) that anyone who falls will end up dying. Children need this specificity to process without developing new fears.

Ask them what they need. When they articulate it – provide it. When they can't communicate their needs – do a continuous trial and error until they feel calmer. Sometimes this means tolerating behaviour you'd normally address differently.

Give them an abundance of love (even when this feels near impossible with what you are going through). Physical comfort releases oxytocin, which literally counteracts stress hormones.

Keep normal routines & boundaries for consistency. Even the harsher ones. The predictability creates safety when their emotional world feels chaotic.

Show your emotions - normalise it so they can feel them too. Verbalise it: 'I feel sad because I am thinking about Grandmarina. She was wonderful & I'll miss her'. Don't forget the positives too: 'I feel really upbeat today, the sun is shining & I'm looking forward to our picnic lunch'. Modelling emotional expression gives them permission for their own.

Allow them control: let them do the food shopping with the little trolleys, let them choose an activity, ask them for their suggestions and try to honour them. Grief can make children feel powerless – giving choice where possible helps restore their sense of agency.

Empower them, don't minimise it. They'll show you how incredibly amazing, loving, resilient, emotionally intelligent, rational, caring and brilliant they are.

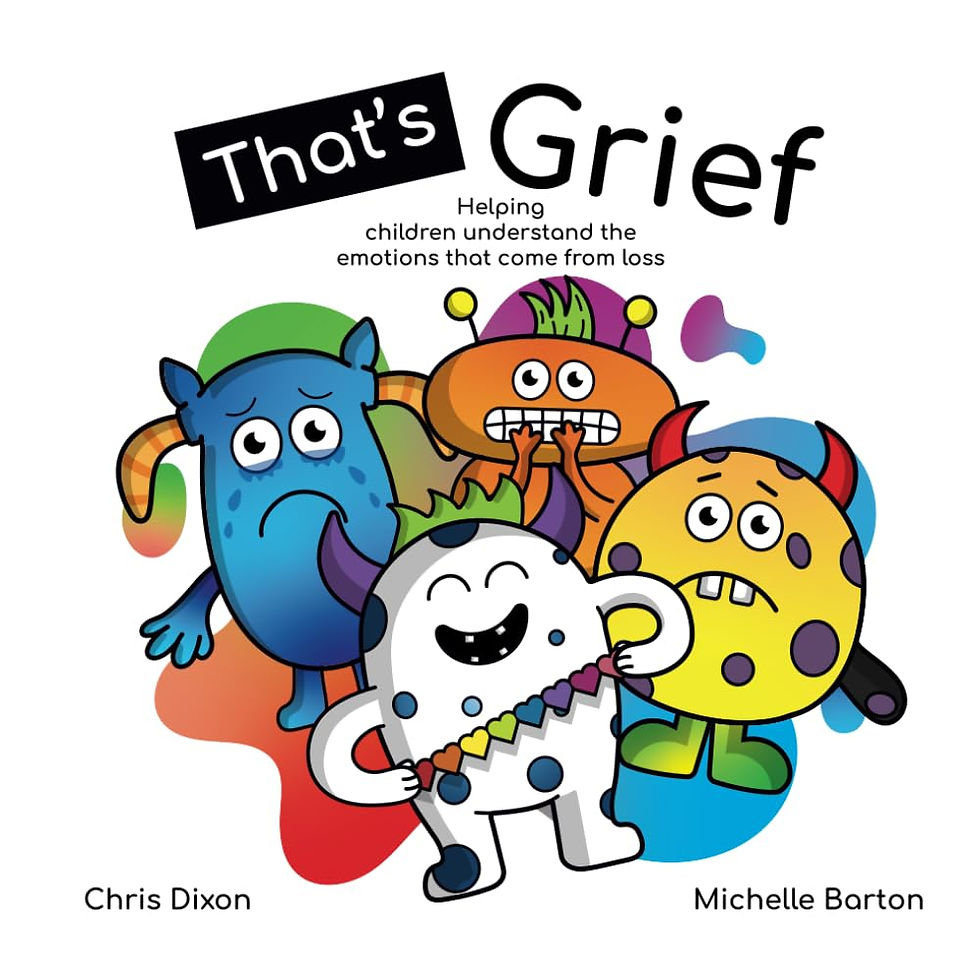

Read child friendly books on grief – they help us adults as much as the kids! (An excellent one, we've read many times is pictured below)

For friends, family and other supporters

If you know someone navigating grief with children, here's what I have found helps:

Be normal! Do normal things.

If the children mention their relative dying, don’t ignore it (with fear of how to respond), just ask questions, see if they want to chat.

Be patient with behaviour changes. That formerly well-mannered, confident child going absolutely nuts, or seeming shy – they're communicating distress the only way they know how.

What I am glad I found out earlier rather than later: children’s developing brains are literally being shaped by how we help them navigate this loss. The neural pathways forming now will influence how they process difficult emotions for years to come. By supporting them through grief openly and lovingly, we're not just helping them through today's pain – we're teaching them healthy emotional processing for life.

Grief is messy, unpredictable, and looks different for every child. The most important thing I've learned is to try my best to stay present and try my best to be patient with both of them.

And when it’s too much, I reflect on my own, and then with them. And I remember that these difficult moments are also opportunities for deep connection and growth.